European Copyright Law, from the Printing Press to the Digital Age – A Journey of Constant Change

By Dr. Mark Hyland

- IMRO Adjunct Professor of Intellectual Property Law at the Law Society of Ireland

- Lecturer in International Intellectual Property Law, Bangor University Law School, Wales

Introduction

The principal objective of this paper is to highlight the evolution of copyright since the emergence of the movable type printing press (1436 AD) right up to the present day. It will be seen that copyright has proven to be a flexible tool in the context of protecting a diverse range of works. In the case of both Ireland and the EU, 2019 was a particularly significant year as new legislation was adopted in the field of Copyright Law. The news laws attempt to modernise Copyright Law, domestically (Ireland) and regionally (EU). My paper also looks at copyright and Copyright Law from a historical perspective. Unlikely as it may seem, Gutenberg’s printing press was a key technological disruptor of its time. The new invention made the reproduction and mass circulation of literary works possible for the first time. But it also raised the spectre of illegal copying and therein sowed the seeds for a novel notion, – copyright. No historical account of copyright would be complete without reference to and treatment of the matriarch of copyright statutes, the Statute of Anne (1710). Adopted in Britain, during the reign of Queen Anne, this law only offered a maximum of 28 years of copyright protection. Nowadays, the general term of copyright protection is life of the author plus 70 years and this fact alone demonstrates clearly how copyright has evolved so much since the eighteenth century. The final part of my paper focuses on technological disruptors which challenge copyright. Special attention is given to artificial intelligence as it is likely to have important implications for copyright ownership.

What is copyright?

Oh, Copyright is a wondrous thing!

It is a very diverse right and has, in fact, many different ‘personalities’.

To start with, copyright is one of the principal intellectual property rights (IPRs) and exists alongside patents, trade marks, industrial designs and trade secrets. IPRs are designed to protect creations of the mind and these creations may be inventions, literary and artistic works, unique names, symbols or images or, indeed a design highlighting the ornamental aspects of a work.

Subsumed into the broad field of Intellectual Property, copyright’s raison d’être is, like the other IPRs, to incentivise and protect creativity and innovation. Copyright is a legal right and that legal right is founded on domestic law, which is heavily influenced by regional (or, EU) law, which, in turn is influenced by multilateral copyright law. Ireland’s primary piece of copyright legislation is the Copyright and Related Rights Act (2000) (CRRA). This was supplemented last year by the Copyright and Other Intellectual Property Law Provisions (2019). In the UK, the primary piece of copyright legislation is the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act (1988) (CDPA). A good example of regional Copyright Law is last year’s Copyright Directive – Directive (EU) 2019/790 on Copyright and Related Rights in the Digital Single Market. EU Member States are required by law to implement the provisions of this Directive into local law by 7 June, 2021. As regards multilateral or international copyright law, the Berne Convention (1886) is a particularly good example. It sets out minimum levels of protection for international copyright works. Other examples of multilateral copyright conventions/treaties are the two WIPO copyright treaties (WIPO Copyright Treaty and WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty) and the Rome Convention for the Protection of Performers, Producers of Phonograms and Broadcasting Organizations. Incidentally, the TRIPS Agreement (administered by the WTO) concerns IPRs generally. ‘TRIPS’ stands for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property. This Agreement came into effect on 1st January, 1995 and it is the most comprehensive multilateral agreement on IP. It established minimum international standards of IPR protection.

Like the other IPRs, copyright is an exclusive right, with these rights accruing exclusively to the copyright holder. Copyright’s two distinct set of rights, economic and moral, accrue to the copyright holder.

Depending on your personal philosophy, copyright is either a monopoly or, a partial monopoly. Another term for ‘partial monopoly’ is quasi monopoly. If you are leaning more towards the notion of “quasi monopoly”, then the term “soft IP” is appropriate, to distinguish copyright from the harder IPRs, such as patents, trade marks and registered design rights. These are true monopolies, founded on a system of formal registration.

Under Irish Copyright Law, copyright is described as a property right. The situation is the exact same under UK Copyright Law. As a property right, copyright works may be assigned, licensed or bequeathed. In other words, these works may may be sold, lent or left in a will by the copyright holder.

Staying with the notion of property, copyright works are both IP assets and business assets. Generally referred to as “intangible assets”, copyright works are frequently converted into tangible assets by their owners. Nowadays, 80% of corporate value is represented by intangible assets and that statistic emanates from none other than the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) itself![1] [2]

Interestingly, in some quarters, copyright is described as a negative right in that the holder may use copyright in a negative way to prevent third parties from doing certain things with/to the protected work. This notion of negative right ties in with the restricted acts (or, acts restricted by copyright) contained in Sct 37 of the CRRA. These important economic rights such as the reproduction right, the right to make available to the public and the adaptation right are the exclusive preserve of the copyright owner. He or she has the exclusive right to undertake such rights or to prevent third parties from undertaking these acts. Naturally, the copyright owner may authorise third parties to do one or more of the restricted acts but they require his/her authorisation before they undertake the acts.

Copyright by implication and Intellectual Property by specification are protected as a fundamental right under the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. The relevant provision of the Charter is Article 17 concerning “right to property”. Interestingly, the references within Article 17 (1) are to “possessions”. Article 17 (2) of the Charter is much more explicit. It states clearly that “Intellectual Property shall be protected”. It is interesting to note that Article 17 of the Charter has its historical origin in Article 1, Protocol 1 of the European Convention for the protection of Human Rights. Article 1, Protocol 1, provides that :

“Every natural or legal person is entitled to the peaceful enjoyment of his possessions”

It is clear from the Charter and the Convention that the demarcations between “intellectual property”, “property” and “possessions” are quite thin indeed.

What is the objective of copyright?

Copyright Law ensures that authors and creators obtain a reward for their intellectual efforts. Sweat of the brow must be rewarded! Copyright ensures that musicians, authors, software writers, movie directors, photographers, architects and sculptors (to name but a few) can all rely on a high level of legal protection for their creative works. Moreover, the duration of protection is impressive too with life of the author plus 70 years being the period of protection in most but not all cases. This lengthy period of protection incentivises creativity, with some copyright works easily capable of spanning a number of generations, depending of course on how long the copyright holder lives for.

For a country such as Ireland, the tangible legal protection offered by copyright to creative works (broadly defined) is of crucial importance. This is particularly true in the context of the ICT sector. Ireland has become a global tech hub and now ranks as the world’s second biggest exporter of software. Sixteen of the top twenty global technology firms have an operation in Ireland. These include the likes of Microsoft, Google, Apple and Facebook.

Ireland’s vibrant creative industry is another significant beneficiary of strong copyright protection. This particular sector is multi-facetted and encompasses such elements as music, performing and visual arts, film, TV, video, radio, photography, advertising, architecture, marketing, crafts, design (whether it be product, graphic or fashion in nature), publishing, museums, galleries and libraries.

The ubiquity of copyright works

IP is truly ubiquitous. It exists all around us. It is omnipresent. As a sub-set of IP, copyright-protected works are also ubiquitous. The operating system on a smartphone, tablet, laptop and PC will be protected by copyright. Newspapers, magazines and novels are covered by copyright as they constitute literary works. Movies fall under the protection of copyright. Music is protected. Photographs and paintings avail of copyright protection as do dramatic works such as choreographic works or, works of mime. One of the four classical groups of protected work, artistic works, is very broad indeed. In Ireland, this category of work encompasses such things as photographs, paintings, drawings, diagrams, maps, charts, plans, engravings, etchings, woodcuts, collages, sculptures, works of architecture and works of artistic craftsmanship.

Interestingly, a work does not have to be particularly ‘fancy’ in character to attract copyright protection. Mundane things, too, can be copyright-protected. Examples include: technical reports, manuals, promotional literature and advertising.

A History of Copyright

The Land of Saints and Scholars

It may come as a surprise to some but one of the first known disputes over ownership rights to the printed word occurred in Ireland in approximately 560 AD. And, who knows, but this dispute may have contributed in a small way to the development of copyright as a general principle.

The dispute involved two saints though arguably one was less saintly than the other and he ended up paying a high price for his unsaintliness!

The protagonists were St Colmcille (the prolific scribe) and St Finnian of Moville. Colmcille and his team of industrious monks were based at Durrow, Co Laois, where they copied all the sacred texts they could get their hands on for wider dissemination. The operation was the sixth century’s answer to the Google book digitisation project.

Finnian was Colmcille’s mentor and he returned to Ireland from Rome with a prized volume of the Vulgate, Jerome’s translation of the Bible. Being a bit of an aesthete, Colmcille was naturally keen to make copies of that too. You could say that Colmcille coveted his neighbour’s Vulgate!

Wary of his protégé, Finnian would not give access to the manuscript. So, Colmcille transcribed the book surreptitiously until the older man discovered the misdeed and demanded the copy. An unholy row broke out between the saints and their dispute was referred to the supreme court at Tara and the High King himself, Diarmaid, found in Finnian’s favour. Delivering a famous ruling, King Diarmaid summed up the judgment in one line:

“to every cow its calf, to every book its copy”

The judgment was even more apt when one considers that judgments at the time were written on vellum (fine parchment made originally from the skin of a calf). So the cow/calf analogy could not have been more appropriate.

However, the story gets better!

Colmcille, the defendant in the case did not appreciate the beauty of King Diarmaid’s judgment and sadly the dispute escalated into the Battle of Cul Dreimhne in 561 AD. By all accounts, the battle was eclectic to say the very least and had a fascinating admixture of politics, religion, death and …….hurling!

This Battle of Cul Dreimhne became known as the “Battle of the Books”. Sadly, it cost 3000 lives and also resulted in Colmcille being banished into exile o expiate his guilt. His punishment was to convert 3000 pagans to Christianity, to make up for the 3000 lives lost on the battle field.

Given that this very primitive (or pioneering) copyright ruling resulted in the death of 3000 men and, at least one calf (!), it is fair to say that it was a very significant judgment.

The matriarch of copyright statutes – the Statute of Anne

The first ever fully-fledged copyright statute in the world entered into force in Great Britain on the 10th April, 1710, having been enacted the previous regnal year. Its title: the Statute of Anne.

Well, that was its short title! Its long title was,

An Act for the Encouragement of Learning, by vesting the Copies of Printed Books in the Authors or purchasers of such Copies, during the Times therein mentioned.

Under this statute, the duration of copyright protection was 14 years, but that period could be extended by a further 14 years to give an absolute maximum duration of protection of 28 years. Works already in print at the coming into force of the statute could avail of 21 years of protection.

Sometimes referred to as the matriarch of copyright laws, this Act was a real milestone as it moved the power away from the printers and towards the authors. In recognising that authors should be the primary beneficiaries of copyright law, the Statute of Anne diluted the power and influence of the London Stationers’ Company which had achieved a monopoly on the printing of books and was regulated by the Court of Star Chamber. The Statute of Anne proved to be a catalyst for copyright legislation internationally as similar laws were enacted in Denmark (1741), the United States (1790) and France (1793).

But the historical roots of copyright can be traced back to the fifteenth century. In that century, two technological developments revolutionised book production in Europe. Firstly, paper became popular as a writing material, gradually supplanting vellum, Secondly, the movable type printing press was invented by the German goldsmith/blacksmith/metalworker Johannes Gutenberg in 1436 AD.

Returning to the first development, paper …, paper’s growing popularity (in the fifteenth century) was helped greatly by the expansion of paper mills from the Iberian peninsula, France, Holland and Germany. The first paper mill in England was built in 1490 near Hertford. By the end of the fifteenth century, paper making had commenced in both Poland (1491) and Austria (1498). This economic trend intensified in the subsequent century, with paper making spreading to Russia (1576) and Denmark (1596).

The surname Gutenberg is synonymous with the second development, the invention of the movable type printing press. Johannes Gutenberg was born in Mainz, Germany, but moved to Strasbourg, France, to perfect his work on the printing press. Gutenberg had a keen eye for commercial opportunity and foresaw strong market potential for the printing of indulgences, the slips of paper offering written dispensation from sin that the Church sold to fund crusades and church building. Whether Gutenberg intended to sell the paper indulgences to fellow citizens or the Catholic Church is not clear.

Prior to the emergence of the printing press there were no real concerns about illegal copying of books as all copying was done by hand. Copying of manuscripts was certainly not for the faint hearted. It was carried out by either secular or monastic scribes and the process was extremely tedious and time-consuming. Unsurprisingly, illegal copying of books was extremely rare before the invention of the printing press.

But, the printing press proved to be one of the earliest technological disruptors. Movable type was truly revolutionary as it enabled the production of a large number of copies quickly and economically, leading to a far wider distribution and accessibility of the printed word. However, the downside to this progress was that the new invention could also be used to carry out illegal printing.

There are two fascinating statistics from this period.

- Before the invention of movable type printing, the number of books in all of Europe numbered in the thousands, but, within 50 years of its invention, the number approached 10 million.

- In 1424 AD (12 years before the invention of the printing press), Cambridge University’s entire collection of 122 books constituted one of the largest libraries in Europe at the time!

The evolution of Copyright Law through legislation

Naturally, a country’s legislature has a key influence on the type of copyright regime that prevails domestically. Ireland’s first Act covering copyright was adopted in 1927. However, this piece of law was not copyright exclusive. The Industrial and Commercial Property (Protection) Act (1927) concerned patents, trade marks, designs and copyright. Our primary piece of copyright legislation – the CRRA – was adopted in 2000. Ireland’s most recent piece of copyright legislation, the Copyright and Other Intellectual Property Law Provisions Act (2019)[3] aims to modernise Irish Copyright Law and reduce barriers to innovation in the digital environment. In addition, this Act implements some important copyright exceptions. These exceptions refer to the following: caricature, pastiche and parody (which are actually provided for in the 2001 Information Society Directive),[4] education (illustration for teaching, scientific research and distance learning), news reporting and, text and data mining for non-commercial research. Another important change introduced by the 2019 Act is to extend the jurisdiction of the District and Circuit Courts to include certain IP claims. This is to facilitate lower value IP infringement cases being brought before these courts. The Circuit Court may now hear copyright actions where claims are in excess of €75,000, while the District Court can hear claims with a value of up to €15,000. As a result, infringement actions by copyright owners will now be heard quicker and will incur lower legal costs than if proceedings were brought in the High Court.

Ireland’s domestic Copyright Law will evolve again soon as our country goes about the task of transposing the 2019 Copyright Directive into domestic law. As part of this process, the Department of Business, Enterprise and Innovation ran a consultation process last September (ending 23rd October, 2019) seeking the views of stakeholders and interested parties on the transposition of the Directive. This first consultation process concerned five provisions of the Directive, Articles 13-17 inclusive. Article 17 (previously Article 13) is the provision intended to address the issue of the ‘value gap’ in the digital market. The value gap is the mismatch between the value that intermediaries (usually online content sharing platforms) extract from copyright works (such as music) and the value that is returned to the rightsholders. This consultation process along with future planned consultations covering other provisions within the 2019 Copyright Directive demonstrates how the Irish government takes on board the views/opinions of stakeholders and interested parties during the transposition process. In essence, this means that the next evolution of Irish Copyright Law should be influenced by organisations and individuals that work in industries/sectors directly affected by copyright laws and policies.

The Complex Relationship Between Copyright Law and New Technologies

Copyright Law and new technologies have a long history, arguably dating back to the Gutenberg printing press of the fifteenth century. New technologies provide new tools for creative expression and new vehicles for sharing those works.

But, sometimes, they also disrupt existing copyright regimes, as seen with the piano (late 1800s), radio (1920s, 30s), cable television (1960s/70s) photocopying (1970s) home video cassette recorders (1970s, 80s) and of course digital downloading and streaming technology (today).

Emerging technologies continue to raise novel questions for Copyright Law. From the printing press to the internet, emerging technologies have provided new tools for expanding forms of creative expression and ways to share that expression.

Technological leaps always create disruption. IP and disruptive technology will now need to be contemplated together and the likes of artificial intelligence (AI), the internet of things (IoT), 3D printing, blockchain and robotic artistics are all market disruptors and change the products and services that businesses are able to provide.

Demystifying Artificial Intelligence (AI)

The term “artificial intelligence” has been around since the 1950s.

It was coined by a group of researchers from a variety of disciplines who came together to clarify and discuss concepts around the notion of thinking machines, the sort of machines that would later go on to beat humans at games like chess, poker and Go. Deep Blue’s victory over the chess grandmaster, Gary Kasparov, in 1997 is a good example of the triumph of AI over a human chess champion. Scientists at IBM developed Deep Blue, the chess-playing computer and in the crucial sixth game of their match, Kasparov resigned after 19 moves.

For some, artificial intelligence remains a nebulous term, often difficult to define. In simple terms, it can be described as machines capable of “intelligent behaviour” allowing for the fact that it is sometimes difficult to define what constitutes “intelligent behaviour” itself. AI could also be defined as the simulation of human intelligence processes by machines, especially computer systems.

How does artificial intelligence impact intellectual property?

AI is increasingly driving important developments in technology and business. It is being employed across a range of industries, from telecommunications to autonomous vehicles.

Increasing stores of big data and advances in affordable high computing power are fueling AI’s growth. AI has a significant impact on the creation, production and distribution of economic and cultural goods and services. Since one of the main aims of the IP system is to stimulate innovation and creativity in the economic and cultural systems, AI intersects with IP in a number of ways.

In September 2019, WIPO held a Conversation on IP and Al bringing together member states and other stakeholders to discuss the impact of Al on IP policy, with a view to collectively formulating the questions that policymakers need to ask. Significantly, three months later, WIPO began a public consultation process on AI and IP policy. It published its Draft Issues Paper on Intellectual Property Policy and Artificial Intelligence (dated 13th December 2019) and called for comments from the widest-possible global audience. It is the latest step by WIPO to address the ongoing interaction between AI and the IP system, including the use of AI applications in IP administration.

In the section on copyright and related rights in the Drafts Issue Paper, the theme of authorship and ownership is highlighted.

The point is made that AI applications are capable of producing literary and artistic works autonomously. But, this capacity raises major policy questions for the copyright system, which has always been intimately associated with the human creative spirit and with respect and reward for and encouragement of, the expression of human creativity. The policy positions adopted in relation to the attribution of copyright to AI-generated works will go to the heart of the social purpose for which the copyright system exists. If AI-generated works were excluded from eligibility for copyright protection, the copyright system would be seen as an instrument for encouraging and favouring the dignity of human creativity over machine creativity. If copyright protection were accorded to AI-generated works, the copyright system would tend to be seen as an instrument favouring the availability for the consumer of the largest number of creative works and of placing an equal value on human and machine creativity.

To stimulate comments, the Drafts Issue Paper poses the following thought-provoking questions:

- Should copyright be attributed to original literary and artistic works that are autonomously generated by AI or, should a human creator be required?

- In the event of copyright being attributed to AI-generated works, in whom should the copyright vest? Should consideration be given to according a legal personality to an AI application where it creates original works autonomously, so that the copyright would vest in the personality and the personality could be governed and sold in a manner similar to a corporation?

- Should a separate sui generis system of protection (for example, one offering a reduced term of protection and other limitations, or one treating AI-generated works as performances) be envisaged for original literary and artistic works autonomously generated by AI?

The creation of works using AI could have very important implications for Copyright Law. But the overriding question is: who owns creative work generated by artificial intelligence? This is not just an academic question but a very practical one too as things like music, journalism and gaming have all been generated by AI.

There is a growing body of works generated by computers. One particularly good example is the artwork titled “The Next Rembrandt”. It was unveiled in Amsterdam in 2016. Interestingly, the portrait was not a long lost painting of the Rembrandt van Rijn, the well known Dutch artist from that country’s Golden Age (i.e. 17th century). Rather, it was a new artwork generated by a computer that had analysed thousands of works by the 17th century Dutch artist, Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn. . Machine learning was deployed by a consortium of data scientists, engineers and art historians from Dutch universities, art galleries and museums. It analysed and reproduced technical and aesthetic elements in Rembrandt’s works to include colour, lighting, brush strokes and geometric patterns. The final 3D printed painting is based on just over 162,000 Rembrandt painting fragments. The end result was a portrait based on the styles and motifs found in Rembrandt’s art but produced by algorithms. Other examples of works generated by computers include a novel written by a Japanese computer program in 2016 that reached the second round of a national literary prize. Deep Mind, the Google-owned AI firm has created software that can generate music by listening to recordings. Other projects have seen computers write poems, edit photographs and even compose a musical.

In theory, some of these works could be deemed free of copyright as they were not created by a human author. It is not an exaggeration to say that machine learning software generates truly creative works without human input or intervention. AI is not just a tool. While the algorithms are programmed by humans, the decision-making – the creative spark, if you will, comes almost entirely from the machine.

If these AI-generated works were deemed to be free of copyright, then said works could be freely used and re-used by anyone. That would spell very bad news for the companies selling the works. Hypothetically, an individual or company could invest very significant amounts of money in an AI system that generates music for video games only to find that the music is not protected by Copyright Law and can be used without payment by anyone in the world. Were copyright protection to be denied in such a scenario, then it is very likely that such a decision would have a chilling effect on investment in automated systems. If developers doubt whether creations generated through machine learning qualify for copyright protection, what is the incentive to invest in such systems?

Legal Options

There are at least two ways in which Copyright Law can deal with works where human interaction is minimal or non-existent. It can either deny copyright protection for works that have been generated by a computer or it can attribute authorship of such works to the creator of the programs.

While conferring copyright in works generated by AI has never been specifically prohibited (to my knowledge), there are indications that the laws of many countries are not amenable to non-human copyright. A good example is the U.S. Copyright Office’s declaration that it will “register an original work of authorship, provided that the work was created by a human being”. This stance flows from case law e.g. Feist Publications v Rural Telephone Service Company, Inc 499 U.S. 340 (1991) which specifies that copyright law only protects “the fruits of intellectual labor” that “are founded on the creative powers of the mind”. A similar approach is evident in Australia. There, the 2012 Federal Court of Appeal ruling in Acohs Pty Ltd v Ucorp Pty Ltd [2012] FCAFC 16 (2 March, 2012) is instructive. The court held that a work generated with the intervention of a computer could not be protected by copyright as it was not produced by a human.

There is also the important 2009 ruling from the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU), C-5/08, Infopaq International A/S v Danske Dagblades Forening. There, the most senior court in the EU ruled that copyright only applies to original works and that originality must reflect the “author’s own intellectual creation.” This is usually understood as meaning that an original work must reflect the author’s personality, which clearly means that a human author is necessary for a copyright work to exist.

If the ownership conundrum is viewed from the perspective of legislation, the situation becomes quite complicated as the laws on this issue differ greatly from country to country. The fact that this area is not governed by international copyright treaties does not assist either.

In certain European countries such as Spain and Germany, the domestic law implies that only works created by a human can be subject to copyright protection. In countries such as Ireland, the UK, Hong Kong (SAR), India and New Zealand, authorship vests in the programmer, ie the person by whom the arrangements necessary for the creation of the work are undertaken.

Under Ireland’s CRRA (Sct 21), the author in the case of computer-generated works is “the person by whom the arrangements necessary for the creation of the work are undertaken”. A similar approach is adopted in the UK and that is encapsulated by Sct 9 (3) of their CDPA.[5]

AI and some crystal ball gazing

If the copyright/AI relationship appears complex now, it is almost certain to get more complex in the years ahead. This is due to the fact that AI tools are being used more and more by artists. In addition, machines are getting better at reproducing creativity, making it more difficult to establish whether an artwork has been made by a human or a computer. In some cases of AI algorithms capable of generating a work, the human being’s contribution to the creative process may simply be to press a button so that the machine can do its own thing. There are already several text-generating machine learning programs out there, and while this is an ongoing area of research, the results can be astounding. A PhD student at Stanford, Andrej Karpathy taught a neural network how to read text and compose sentences in the same style, and it came up with Wikipedia articles and and lines of dialogue that resembled language used in the works of Shakespeare.

A combination of significant advances in computing and the impressive amount of computational power becoming available may well make the distinction between machine-generated and, human-generated moot. At that point, legislators and policy-makers will have to decide what type of protection, if any, we should give to emergent works created by intelligent algorithms with little or no human intervention. There may be merit in approaching the ownership issue on a case-by-case basis. In the English case of Nova Productions v Mazooma Games [2007] EWCA Civ 219, the Court of Appeal had to decide on the authorship of a computer game. The court declared that a player’s input “is not artistic in nature and he has contributed no skill or labour of an artistic kind”.

Conclusions

Ever since the enactment of the Statute of Anne in 1710, copyright and Copyright Law have had to adapt to remain relevant. The rationale for the adoption of the 2019 EU Copyright Directive is set out clearly in recital (3) of that legal instrument. That recital refers to “rapid technological developments” which transform the way works and other subject matter are created, produced, distributed and exploited. Recital (3) also refers to the need within the EU to have copyright legislation that is “future-proof” so as not to restrict technological development. The Directive is clearly part of the EU’s Digital Single Market but it is also the cornerstone of a new modern European copyright framework. The new Directive represents adaptation and supplementation of the existing Union copyright framework while a high level of protection of copyright and related rights is maintained at all times. A good example within the 2019 Directive of copyright’s flexibility is the presence of the all-important copyright exceptions/limitations (See: Articles 3-7 of the Directive). These exceptions afford tangible benefits to the fields of scientific research (text and data mining for the purpose of scientific research), the education sector (digital and cross-border teaching activities) and cultural heritage (preservation of cultural heritage). Through the flexible and pragmatic application of the reproduction right, these exceptions (which are all mandatory in nature) ensure that research institutes (to include universities and libraries), libraries, museums, film or audio heritage institutions, educational establishments and indeed the individual EU citizens that use said facilities benefit in a tangible way.

Copyright remains compelling and relevant due to its willingness to be flexible and adaptable. Often, the adaptations are necessitated by technological advances. So long as EU Copyright Law strives to be future-proof and does not unnecessarily impede technological development, then the copyright/technology relationship is likely to be one of symbiosis rather than antagonism.

Notes:

[1] WIPO is the global forum for IP services, policy, information and cooperation. Established in 1967, WIPO is an agency of the United Nations and its mission is to lead the development of a balanced and effective international IP system that enables innovation and creativity for the benefit of all.

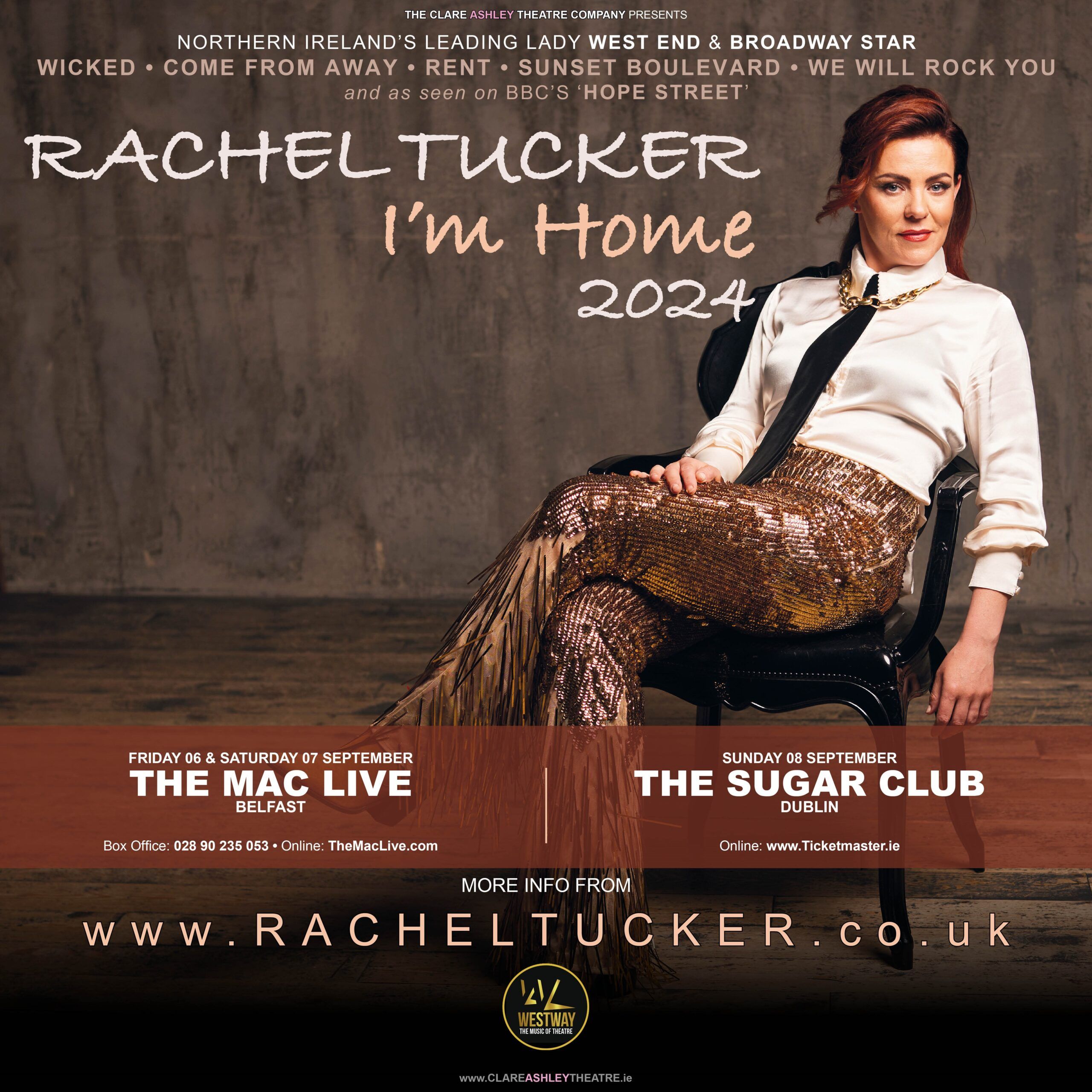

[2] Staying with the theme of corporate or economic value, Ireland’s music industry contributes an impressive €703 million per year to the Irish economy. In addition, the industry provides employment to just over 13,000 people in the State. Source: Deloitte’s 2017 report titled “The Socio-economic Value of Music to Ireland” (commissioned by the Irish Music Rights Organisation).

[3] As of 14th February 2020, all sections of the 2019 Act are in force. See Copyright and Other Intellectual Property Law Provisions Act 2019 (Commencement) Order 2019 (S.I. No. 586 of 2019).

[4] Directive 2001/29/EC of 22 May 2001 on the harmonisation of certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society (often termed the InfoSoc Directive).

[5] What follows is the actual wording of Sct 9 (3), CDPA, “In the case of a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work which is computer-generated, the author shall be taken to be the person by whom the arrangements necessary for the creation of the work are undertaken”

Latest News

Music Creators

- Affinity Schemes

- Join IMRO

- Benefits of IMRO Membership

- IMRO Mobile App

- Members’ Handbook

- About Copyright

- Royalty Distribution Schedule

- IMRO Distribution Policies

- Competitions & Opportunities

- Travel Grant Form

- Irish Radio & Useful Contacts

- Other Music Bodies in Ireland

- Affinity Schemes

- Music Creator FAQs

- International Partners

- International Touring Guide

Music Users

- Do I Need a Licence?

- Sign Up for a Music Licence

- Pay Your Licence Online

- IMRO and PPI Tariffs

- Dual Music Licence Explained

- Music Licences for Businesses

- Music Licences for Live Events

- Music Licences for Broadcast & Online

- Music licences for Recorded Media

- Music Services B2B

- Music User FAQs

- What’s Your Soundtrack Campaign

- Terms & Conditions for IMRO Events Voucher Competition

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Statement

- Disclaimer

- www.imro.ie

- Terms & Conditions

- © IMRO 2024

- Registered Number: 133321

Please select login

For Songwriters & Publishers

For Business Owners